On the Value of Business Architecture

Scott A. Whitmire

April, 2017

There has been an on-going debate about the value of business architecture, with three main groups of participants. Each group has their focus that colors their view of this value. This article discusses those views and provides an alternative point of view that may prove useful.

The first group consists of business architecture practitioners who tend to focus on the models and views we use to describe a business architecture. Their definition of the value naturally focuses on the models and views as providing direct value, if only “the business” would let them practice. Another aspect of this view is the notion that business architecture should be practiced by trained professionals that are part of a business architecture team or program. Today, this group represents the majority of business architecture practitioners.

The second group comprises the business leaders who actually run “the business:” These people listen to the first group describe business architecture and wonder what all the fuss is about. Every description of what a business architect does is very similar, nearly identical, in fact, to what every manager has been taught is their function. They have a point. What they miss, however, is the growing realization that the dirty details of the practice require tools and concepts they haven’t mastered, and don’t have time to use. When you’re in the weeds trying to make the numbers for the month or quarter, you’re not really interested in changing anything, nor do you have time to think much beyond the current period. Long range planning and selecting potential changes to the business operating model fall on senior executives, or worse, business process improvement folks.

This second group can see value in the practice of business architecture, but only if it helps them run the business they have today and makes it easier to identify and manage changes to ensure the business is ready for the future. Oh, and it must do all that and not create a lot of overhead, both in terms of costs and friction.

The third group is just coalescing from a hodgepodge of business leaders, business process professionals, and business and enterprise architects who hear what the business has been saying, see the limitations in the views of the first group, and are trying to address both. The view of this group focuses not on models and views, but on what business architecture, as a practice, can provide to the business. The value of this view is expressed in terms of better business outcomes through tighter links between operations and strategy. The rest of this paper describes this view of business architecture value.

Architects, especially those in information technology and business, are known to focus on definitions (there is a good reason for this, but that’s for another article). In keeping with that tradition, let us start with a definition of the value of business architecture:

The value provided by business architecture is the description and understanding of the links between operational execution and strategic intent. These links are established and maintained by focusing the investment in business changes to those areas that refine and maintain those links.

This definition carries a lot of information. Part of the understanding of those links involves quantifying the relative influence business inputs in the operating model have on various desired business outcomes, usually expressed in financial or customer terms. With this understanding, it is possible to determine where best to make investments in the business given a desired set of changes in business outcomes. I have often expressed this view in my “elevator pitch” for business (and enterprise) architecture: “If you were to set out to double revenue and grow gross margin over the next five years, where would you invest first and why?” Knowledge of the links between operations and outcomes can guide you to the best answers.

I have taken to describing these links and their relative influence as “the plumbing” of the business. The choice of metaphor is deliberate in that some inputs (those parts of the operating model that can be changed) have more influence than others on business outcomes (some inputs can have negative influence on some outcomes), and the plumbing metaphor allows the use of the size of the pipe and direction of the flow to represent the quantification.

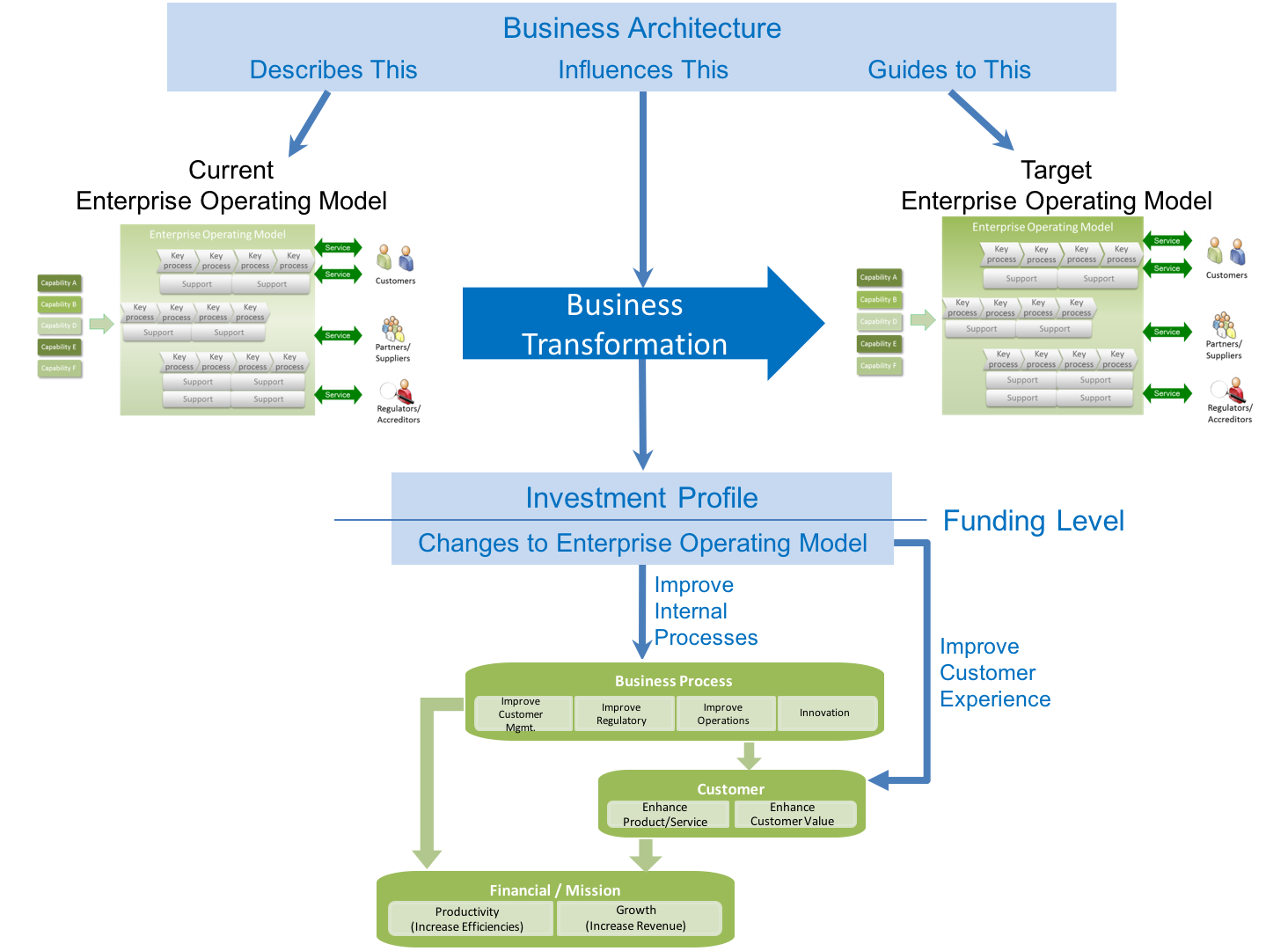

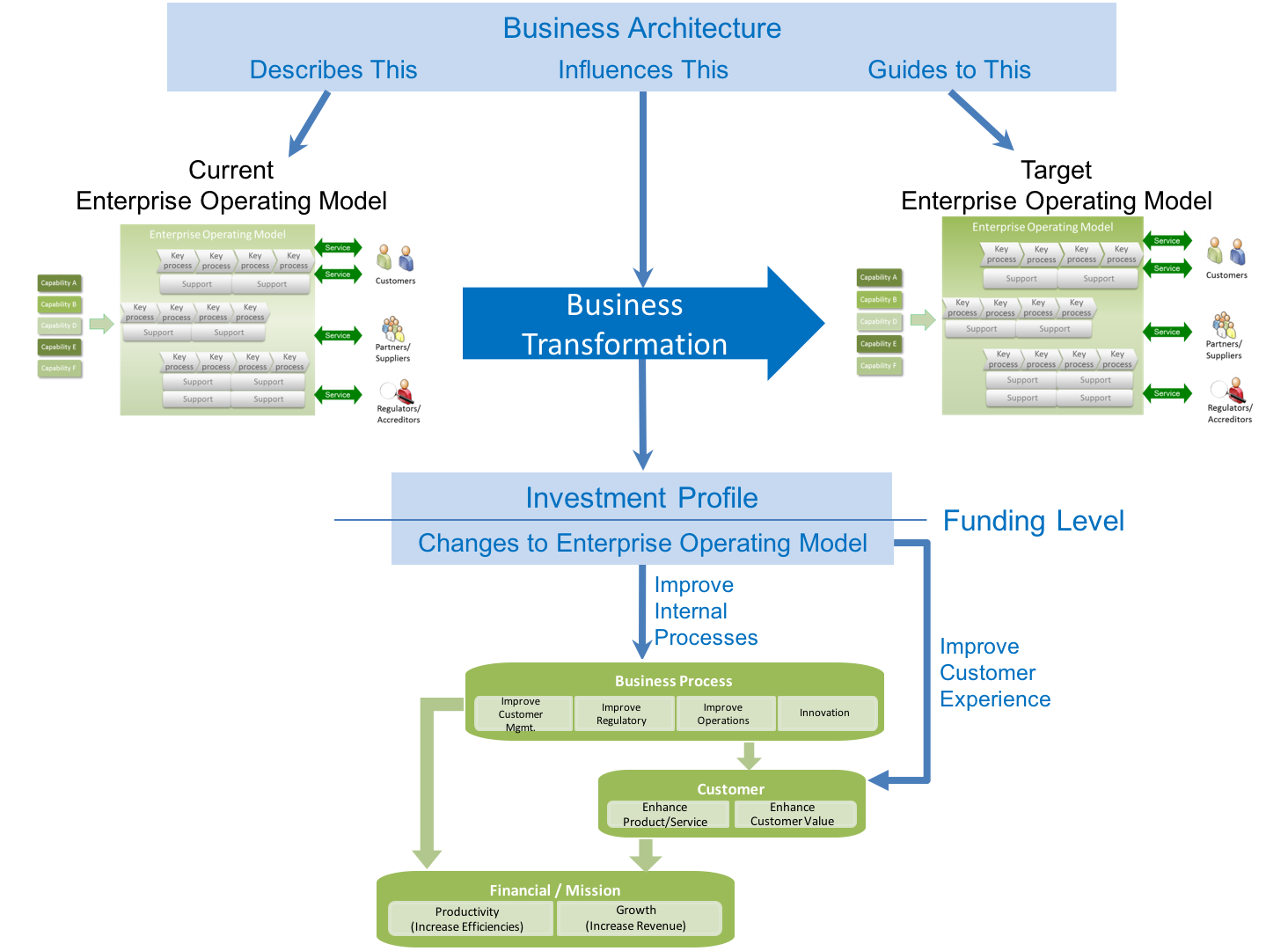

This definition of value also hints at the main purpose of the business architecture practice: To focus investments and manage the investment portfolio to maximize the total return within a risk tolerance profile. This sounds like the kind of goals a manager of a financial portfolio might have, and it should: The portfolio of projects (investments) to change the business operating model is a financial portfolio. This idea is illustrated in the following diagram.

Another aspect of the definition is the focus on business outcomes as the target for practicing business architecture. Better business outcomes is the only reason to take on something like business architecture. Any other focus distracts from the main purpose of the business organization. The real practitioners of business architecture are necessarily the managers responsible for the success of the business. This means all of them, not just the executives. The trouble is, business management has become highly technical, and more time must be spent ensure the organization can meet its future goals, all the while meeting the current goals. If you ask most operational managers what keeps them up at night, it’s the latter: Meeting operational goals, or the numbers for the week, month, or quarter. Those who know the business best, the operational managers, simply do not have the time or energy to focus far into the future. In addition, many of these people fear that changes made to secure a better future will simply make their today more difficult. In fact, the leading cause of failure for business improvement and software projects is the resistance from operations to the changes being imposed by the project.

None of this is to say that models and views are not important. They provide value, but they are not the value. Business architecture professionals do have a place in business, but it isn’t at “the table” where strategy is set. Rather, it is at the side of those responsible for the current operations, helping them focus on the structures they manage to ensure those structures are and remain healthy and capable of implementing future strategies. The full set of these structures comprise the current operating model for the enterprise. The primary task of business architecture is to understand the current operating model, how the model needs to change in the future to meet strategic goals, and how best to get there. Actually getting there is the job of the day-to-day operational managers.

In future articles, we will get into the details of the operating model and how business architecture can help.